In a previous post I discussed the idea of using a player’s expected batting average (xBA) to analyze how “lucky” hitters are getting in terms of BABIP. During this process, I put a lot of thought into what it means for a player to be getting a lot of hits on balls in play; Are they hitting the ball hard? Are balls getting hit into the air, on the ground, or in between? One element I began to consider was the batter’s position in the batter’s box, more importantly, which side of the batter’s box they are standing in.

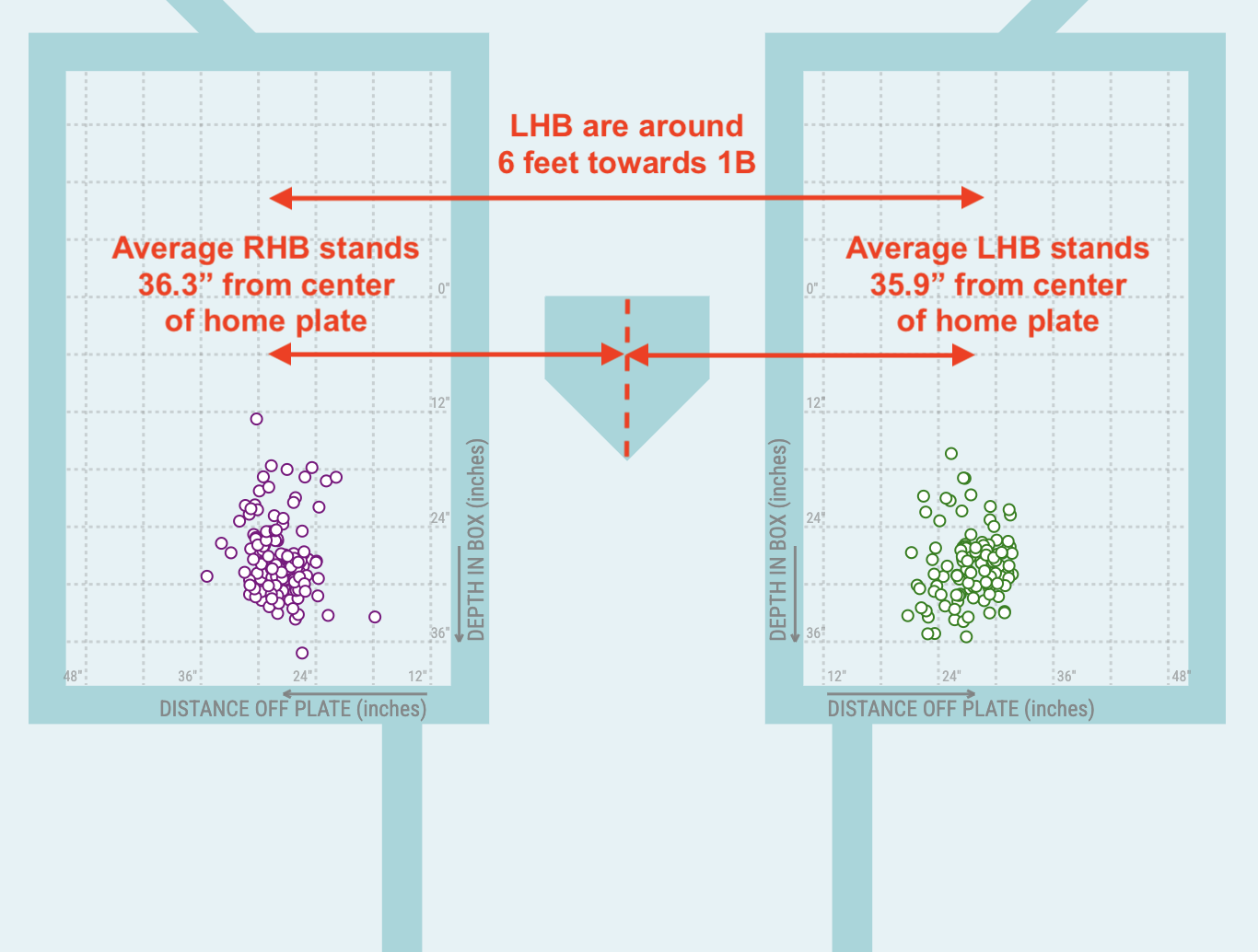

This is incredibly obvious, but because of the dimensions of the baseball field, and the rules stating that players round the bases counter-clockwise, batters who stand on the left side of the home plate (from the pitcher’s perspective) are a little bit closer to 1st base compared to their counterparts standing on the right side:

(the nuances of more ways rounding the bases counter-clockwise has shaped baseball history can be found in Russell Carleton’s book The New Ballgame: The Not-So-Hidden Forces Shaping Modern Baseball)

….but how much of a difference does this physical difference make? Now, thanks to the magic of Statcast, we can deep-dive into the statistics to see if there actually is an advantage.

To first understand this, let’s find out how much of a difference this actually makes, distance and time-wise. This year, Statcast introduced batting stance data, which shows where each batter sets up in the batter’s box (both prior to a pitch and as they swing on a pitch). Among many things, this data shows us how many inches a batter sets up away from home plate. The average right-handed hitter sets up 36.3 inches away from home plate. Remember, this is 36.3 inches away from 1st base directionally. Left-handed hitters set up 35.9 inches away from home plate, which directionally is towards 1st base. Combining the two, the average left-handed hitter is standing nearly 6 feet towards 1st base even before taking a swing:

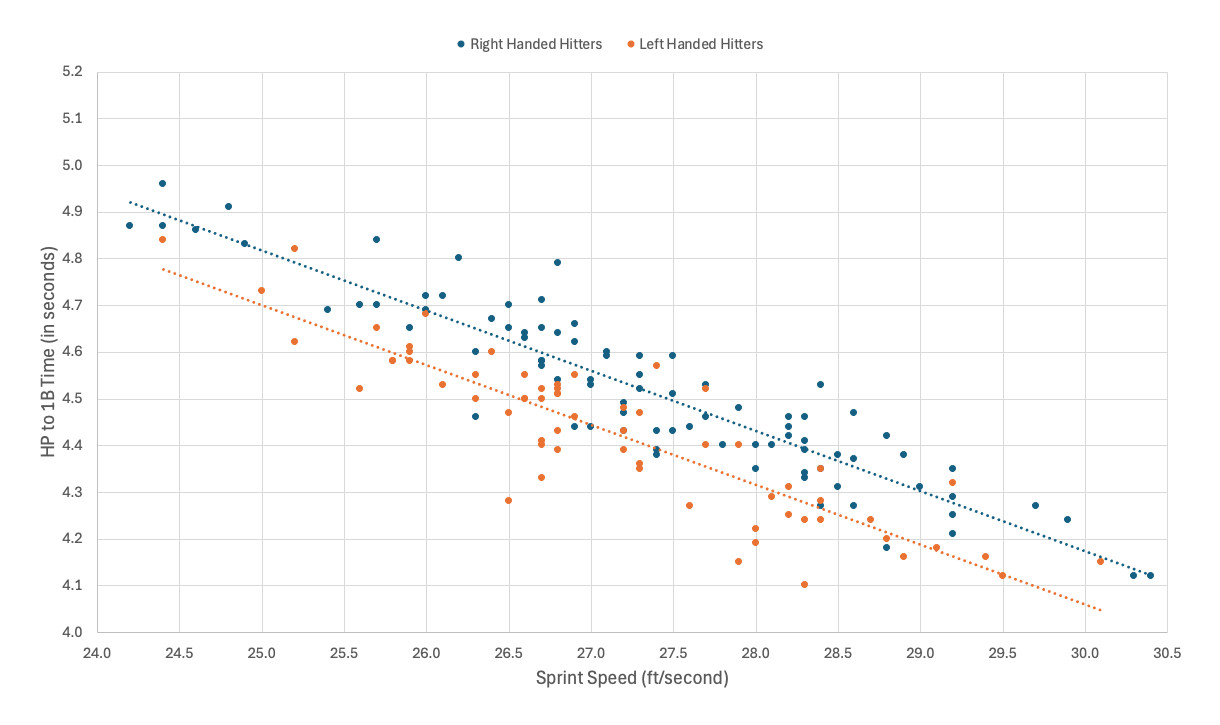

Now that we have the distance advantage calculated, we can look at the time difference this makes in terms of how fast left-handed batters get to 1st base compared to their peers. Statcast tracks both Sprint Speed and HP to 1st Time. Sprint Speed is exactly as it sounds, it measures the fastest tracked times the player is running and gives it to us in feet/second. HP to 1st Time is the average time in seconds it takes for the batter to reach 1st base after hitting the ball. You would assume if you compare two hitters with similar sprint speed – one hitting right-handed and one hitting left-handed – the guy who hits left-handed gets to 1st first. This assumption is true, plotting hitters showing their sprint speed and HP to 1st time, the left-handed hitters consistently show faster times compared to right-handed hitters with similar speed. On average, a left-handed hitter gets to 1st base 0.14 seconds faster, which may not be a lot, but knowing how close a bang-bang play at 1st can be, you can understand why it would matter.

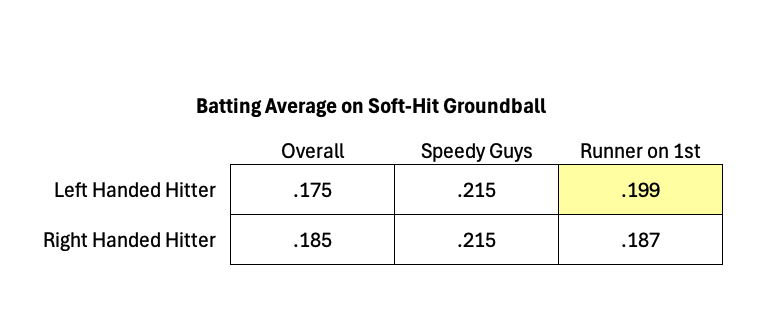

Knowing left-handed hitters are closer to 1st, get faster to 1st, the final assumption is that LHB must have an advantage in beating out groundballs for infield hits. This is not true, and that’s where the paradox comes in. Looking at soft-hit (under 95mph exit velocity) groundballs over the past two seasons (2024-2025), left-handed batters batted .175 on soft-hit groundballs, right-handed batters batted .185 on soft-hit groundballs. So not only do left-handed hitters not have an advantage, they actually do worse. How is that possible?! You ask. Perhaps I didn’t account for the fact that there are a bunch of right-handed hitting slow catchers dragging down the numbers. So I filtered for just hitters with “elite” speed (+90th percentile sprint speed) to see if this would make a difference. Speedy right-handed hitters batted .215 on soft-hit groundballs, and speedy left-handed hitters batted .215 on soft-hit groundballs. So, at least the backwards splits are gone, but there is still no advantage to the lefty.

The explanation for this paradox is rather simple. While the left-handed batter enjoys the closer distance to 1st base, there is also an extra defender on their pull side since the 1st basemen can stay closer to 1st base. While a team can overshift somewhat to a right-handed hitter, they cannot swing their 1st basemen too far from 1st base. The best way to see this is to look at situations where the 1st basemen is having to stay close to the base due to a base runner. When there is a runner on 1st, the left handed hitter bats .199 on soft-hit groundballs.

Unfortunately, there’s not much insight as far as fantasy use goes. I originally thought this would help explain why fast, good contact, right-handed hitting guys like Masyn Winn and Wyatt Langford don’t have higher batting averages compared to left-handed, good contact hitting peers like Sal Frelick and Brice Turang, but it seems the paradoxes neutralizes the physical distance advantage. Sometimes we deep dive, hoping to find some useful data, sometimes we end up with nothing.