PRINCETON, N.J. — Matt Allocco curled from the corner and drove hard to the paint. The move drew two Cornell defenders, leaving forward Caden Pierce all alone under the basket. With the score tied at 71 and under 90 seconds remaining, Allocco dished and Pierce elevated for a go-ahead dunk and the foul, detonating the sold-out Jadwin Gymnasium crowd.

The bucket put Princeton in front for good in a 79-77 win on senior day, moving the Tigers all alone into first place in the Ivy League standings.

“One of the better-executed plays I’ve ever seen,” Princeton coach Mitch Henderson said of Pierce’s and-1. “Huge play.”

What made it more impressive — and clutch — was that it came in crunch time of the second game in as many nights, the waning moments of a back-to-back on Friday and Saturday. Pierce, who played 37 minutes and had a team-high 19 points in Friday’s win against Columbia, followed it with 36 minutes and a team-high 23 against Cornell. Allocco missed the second half on Friday after taking a hard fall and was a game-time decision on Saturday, mustering 19 points in 36 minutes on top of that late assist.

“The Saturday game, as Coach Henderson always says, is just about guts,” said Allocco. “Home or away, it doesn’t really matter on that second day. It’s just about being gritty and tough.”

The Friday-Saturday games have been a near century-long staple of the Ivy League. Most conferences play once midweek and once on the weekend, with two or three days between games. Some will play two games in three days on occasion. Early-season multi-team events and late-season conference tournaments feature back-to-backs, but there’s nothing in the sport as consistent or distinctive as the Ivy’s approach, which exists precisely for the reason you assume.

“We have a philosophy of putting Ivy League games on weekends as much as possible to minimize missed class time,” said Robin Harris, the conference’s executive director since 2009.

Despite an academic motive, the crucible of back-to-back weekends has helped condition those New Jersey nerds on the court as well. Princeton reached the Sweet 16 as a No. 15 seed in last year’s NCAA Tournament, upsetting Arizona and Missouri in the opening rounds. The Tigers graduated their top two leading scorers from that squad, but several core contributors are back. Pierce, a sophomore and versatile forward, has emerged as the team’s second-leading scorer and leading rebounder, averaging nearly a double-double. The younger brother of Indianapolis Colts receiver Alec Pierce and former North Carolina basketball player Justin Pierce was a late bloomer who spent the pandemic sequestered in his basement, working out with a couple Division I athletes who didn’t mind bullying him around.

Fellow sophomore and leading-scorer Xaivian Lee is a spindly combo guard who is dynamic attacking the rim. A Toronto native with dual Canadian-U.S. citizenship, South Korean heritage and a jet-black shag of hair, Lee has nearly 43,000 Instagram followers and is generating some NBA buzz. Princeton was his only D1 offer.

Allocco, the team’s starting point guard and furrow-browed senior leader, had a recent back-to-back on the road in which he played a full 40 minutes in each game and committed zero turnovers.

“That was my dream stat line as a player,” said Henderson, now in his 12th season at his alma mater. At an elite academic university, in a conference that doesn’t offer athletic scholarships, he’s threading the needle with one of the best teams in the country that no one knows about — and looks primed for another Cinderella run this month.

The Ivy League is the smallest conference in men’s college basketball, though even diehard fans pay scant attention until one of the eight member schools pops up as a double-digit seed in their annual office pool. Folks might remember Cornell’s own Sweet 16 run in 2010, or Harvard’s four straight tourney trips last decade under former Duke player Tommy Amaker. Henderson isn’t exactly a household name, but there was an iconic shot of him leaping for joy as a player on Princeton’s 1996 team that upset UCLA as a 13-seed.

Princeton has now had two NCAA Tournament wins as a double-digit seed since the field expanded in 1985: in 1996 and 2023 🐯@PrincetonMBB head coach Mitch Henderson was part of both victories. pic.twitter.com/6j3pTEopck

— CBS Sports College Basketball 🏀 (@CBSSportsCBB) March 16, 2023

Still, the Ivy is more than a high-brow novelty act: It currently ranks 13th out of the 32 Division I conferences in men’s college basketball according to KenPom efficiency metrics, just a couple spots below the West Coast Conference that features Gonzaga and Saint Mary’s. Yale and Cornell are in the top 100 of the NET rankings. Princeton — at 24-3 overall and the favorite to repeat as Ivy League tournament champ this weekend — has played well enough to garner consideration as an at-large team.

The league is being talked about for other reasons these days. Dartmouth’s men’s basketball program voted to unionize in a potential landmark moment that could usher in an era of employment status for college athletes and officially stamp out the amateurism model. But even as one of its members upends an NCAA paradigm that has become increasingly monetized and professionalized, the Ivy League remains more relevant for the ways it hasn’t changed, a conference trapped in amber as the last true bastion of academia in college sports. Epitomized by a handful of teams trying to string together 80 minutes of winning basketball in a little over 24 hours.

Cornell played at Penn on a Friday, then traveled to face Princeton the next day. (Courtesy of Ryan Griffith / Cornell Athletics)

“You know the old analogy of the duck swimming across the lake? On the surface it appears calm and smooth, but underneath, the duck is chopping that water like crazy,” said Chris Mongilia, Princeton’s director of basketball operations. “That’s how it feels on these back-to-back weekends. We do our best to make sure everything is calm and under control, but behind the scenes, we’re paddling like crazy to stay above water.”

Allocco goes by “Mush,” a childhood nickname given by his father because he never shut up. The Hilliard, Ohio, native was a high-school standout whose high-major college interest never materialized, but he was a strong student with an offer from Princeton and family in New Jersey.

Like most Ivy League players and coaches, he arrived completely unaware of the Friday-Saturday gauntlets that awaited in conference play.

“You can’t really talk about or simulate it,” he said. “You really have to go through it. You have to live it.”

The weekend double-headers date back to the old Eastern Intercollegiate Basketball League of the early 1900s, a forerunner to the Ivy League, which was established in 1955. The tradition became commonplace by the late 1950s and soon evolved into standard practice. A couple of the member institutions used to have midterm exams in late January, and the conference had a rule that no athletics program could hold regular-season contests during exam weeks. When the academic schedules adjusted over time, the custom stuck.

Each program has a geographic travel partner: Cornell and Columbia, Harvard and Dartmouth, Brown and Yale, Penn and Princeton. (It’s the same for women’s basketball.) So Cornell and Columbia are always on the road at the same time against the same two opposing travel partners: Cornell plays Penn on Friday, for example, then travels to Princeton for Saturday, or vice versa for Columbia.

In an era of coast-to-coast super conferences, the Ivy’s clustered footprint makes this feasible. Penn, located in Philadelphia, is the southernmost campus. Dartmouth, located in Hanover, New Hampshire, is the northernmost. Every road game in the Ivy is via bus, which can still make for long trips — Penn to Dartmouth is roughly six hours. But travel stresses aside, there’s a rhythm and simplicity to all of it, right down to home teams wearing white home jerseys on Fridays and dark road jerseys on Saturdays to avoid any hurried trips to the laundromat.

“If you play Friday night and you win, you’re excited and happy and now you get to play again Saturday and get after it. And if you lose, you get to turn around and correct it,” said Yale coach James Jones, who’s won six regular-season titles and made three NCAA Tournament appearances in his 24 seasons at the helm. “I like that aspect of the planning, the preparation, the travel. If you can do that and be successful, everything else is easy.”

For decades, the eight teams would play 12 of their 14 round-robin league games on Friday-Saturday back-to-backs, then travel partners would coordinate the home-and-home against each other. Starting with the 2021-22 season, the conference schedule was extended from eight weeks to 10, and each team now plays eight of the 14 league games on back-to-backs, or four Friday-Saturday weekends instead of six. Outside of all eight teams playing on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, there were only three total league games on weeknights this season, and just one since Jan. 9.

The extended schedule lessens the burden in a quantitative sense, but the same pressures and coordinating challenges exist.

Ivy League coaches have to get creative when it comes to film study and scouting reports. At Yale, Jones scouts against the Saturday game on Wednesday and the Friday game on Thursday. At Princeton, Henderson spends Monday and Tuesday on Saturday’s game, then Wednesday and Thursday on Friday’s. But it’s a fluid process. When Penn’s senior leading scorer missed a stretch due to injury this season, longtime coach Steve Donahue had to adjust.

“My team is so young I could only talk about the Friday game,” said Donahue.

Long bus rides and late nights are unavoidable — the four hours between Cornell and Columbia makes it the most dreaded Friday-Saturday road trip, with opposing teams routinely arriving as late as 3 a.m. Saturday — but it also heightens the importance of sleep, rehab treatment and nutrition.

“Less. I do less now,” said Henderson, his coiffed curls a graying reminder of that 1996 photo. He no longer holds a Saturday shootaround when Princeton is on the road for back-to-backs, and emphasizes not getting too high off a Friday win or devastated by a loss that it bleeds into Saturday.

“It’s very mental,” he said.

That’s on top of the players’ notoriously rigorous course schedules. The Ivys are some of the most exclusive universities in the country, with admissions rates as low as 3 to 6 percent. Athletes must qualify academically to be accepted, and because the conference offers no athletic scholarships, the admissions threshold tends to be nearly as demanding as it is for non-athletes.

Pierce and Lee are economics majors. Senior Zach Martini is a New Jerseyan and English major who’s considering law school. Junior sharpshooter and Kevin Garnett impersonator Blake Peters majors in public and international affairs, plays Spanish classical guitar and is fluent in Chinese.

“ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE!”

Blake Peters is FIRED UP as Princeton advances to the Sweet 16! #MarchMadness pic.twitter.com/CvxvH2MT0h

— NCAA March Madness (@MarchMadnessMBB) March 19, 2023

“It’s really about managing your time,” said freshman guard Dalen Davis, a former 3-star prospect out of Chicago who had power-conference offers, listens to Rod Wave and is interested in studying psychology. “Weekdays we have class, and being able to attend classes is just as important as recovery and staying on top of everything. So having weekend games just fits.”

Some of it is still beyond their control. Every Ivy League player and coach has a travel horror story of getting delayed by a snowstorm or the bus driver going the wrong way. Jones once woke up in the middle of the night on a back-to-back trip from Cornell home to Yale, only to realize the bus was headed west instead of east.

“It was criminal,” said Jones. “We got back at like 5:30 a.m. as the sun was coming up. But it was a good thing I woke up, or we might have ended up in Cleveland.”

The struggle is real, but so is the payoff. Mastering the short turnaround is a muscle that doesn’t atrophy, something Princeton noticed in the NCAA Tournament last season when the Tigers beat No. 7 seed Missouri two days after upsetting second-seeded Arizona.

“Our guys had a lot of pop that second game,” said Henderson. “The day off in between, for us it felt like heaven.”

The scene at Jadwin Gymnasium for a back-to-back Ivy League weekend (Courtesy of Ryan Samson / Sideline Photography)

Jadwin Gymnasium features a basketball court tucked within a full-size indoor track, surrounded by portable bleachers. The multi-use building has five sublevels beneath the ground-floor grandstand, a windowless, 1960s bunker with athletics offices, locker and training rooms, tennis courts, and one of the largest fencing facilities in the country.

Friday’s game against Columbia was moderately attended, a crowd of 2,700 giving the oversized arena a wholesome, high-school vibe. Fans mosied courtside during pregame warmups. A local elementary group sang the National Anthem. Players tossed T-shirts into the crowd during the starting lineup introductions. Princeton is one of the richest and most decorated universities in the country, with an endowment of about $35 billion and a long list of distinguished alumni, including James Madison, Alan Turing, John F. Kennedy, Michelle Obama and Jeff Bezos. Yet the men’s basketball program spends roughly $1.7 million annually, or about $10.5 million less than the Arizona men’s basketball budget. When it comes to athletics, the Tigers aren’t exactly keeping up with the Bezoses.

They struggled to keep up with Columbia early in the first half as well. Princeton fell behind 21-12 before the winning DNA kicked in for an 84-70 victory, aided by a career-high 16 points from Davis off the bench and 17 from Peters.

Saturday’s environment was more spirited, with nearly 5,500 fans packing those bleachers to capacity for a first-place battle against a Cornell squad that beat the Tigers in January. The Big Red bused into campus late Friday night after a comeback win of their own over Penn, weathering a flat tire on the drive from Philadelphia. Head coach Brian Earl was a Princeton assistant under Henderson and college teammate on those late ’90s tournament teams.

“I can’t even look at the other sideline. Brian is a great friend,” said Henderson. “It’s very difficult, really not a fun game to coach in.”

Watching it was a different story. Another slow start for the Tigers turned into a back-and-forth barnburner that featured 14 lead changes and a late surge by the home team, which remained unbeaten at Jadwin.

“They are so hard to guard. There are killers at every position for them,” said Earl. “You saw Princeton on a neutral court last year and got a taste of how good they are.”

This year’s team is hoping to show it again, though it will have to take care of business in this weekend’s four-team conference tournament, affectionately dubbed “Ivy Madness.” The at-large chatter is nice, and deserved, but Henderson has no illusions of the Ivy becoming a multi-bid league — as much as he might disagree.

“If we want to go to the NCAA Tournament, we have to win the league. We know that,” he said. “We also know if we can get that chance again, we’re very dangerous.”

But Henderson didn’t want to get ahead of himself. He was more than happy to soak in his team’s two victories in two days. The rest could wait.

“Any time you can get a weekend sweep, it’s really special,” he said.

Especially at home. For Earl and Cornell, there was only the sting of missed opportunity to stew over on the trip back to Ithaca, N.Y., a four-hour drive that gets them home around 3 a.m. So long as the bus doesn’t take a wrong turn.

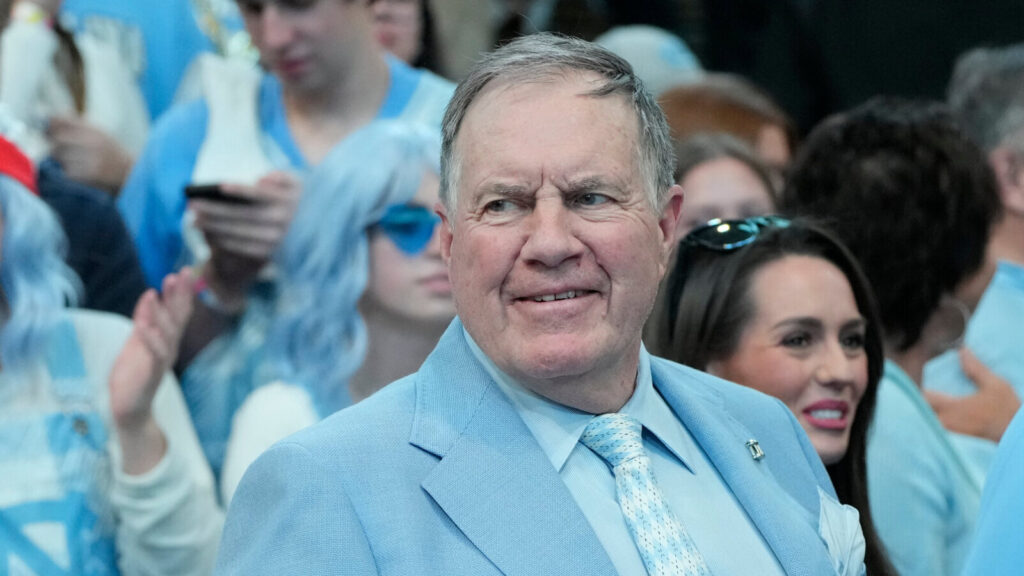

(Top photo of Princeton’s Matt Allocco: Courtesy of Ryan Samson / Sideline Photography)